Or try one of the following: 詹姆斯.com, adult swim, Afterdawn, Ajaxian, Andy Budd, Ask a Ninja, AtomEnabled.org, BBC News, BBC Arabic, BBC China, BBC Russia, Brent Simmons, Channel Frederator, CNN, Digg, Diggnation, Flickr, Google News, Google Video, Harvard Law, Hebrew Language, InfoWorld, iTunes, Japanese Language, Korean Language, mir.aculo.us, Movie Trailers, Newspond, Nick Bradbury, OK/Cancel, OS News, Phil Ringnalda, Photoshop Videocast, reddit, Romanian Language, Russian Language, Ryan Parman, Traditional Chinese Language, Technorati, Tim Bray, TUAW, TVgasm, UNEASYsilence, Web 2.0 Show, Windows Vista Blog, XKCD, Yahoo! News, You Tube, Zeldman

Save money by canceling more software projects, says survey | InfoWorld

Technology insight for the enterpriseSave money by canceling more software projects, says survey 13 Mar 2026, 9:41 am

Enterprises should be more ruthless about cancelling projects. That’s according to project management software company Tempo, which surveyed 667 project planning leaders at the end of last year. It found that those who deployed better scenario planning and acted ruthlessly is assessing a project’s viability would be better off.

According to the survey, 90% of organizations claimed that their projects were aligned across teams. However, Tempo found that expectations didn’t always meet reality: Only 70% of projects delivered a meaningful return on investment, and over 33% of projects were cancelled or stopped early due to misalignment or lack of ROI.

Companies that deployed scenario planning software had a 17-percentage-point advantage in delivering ROI, according to the survey. Paradoxically, those with more mature planning processes cancelled more projects, Tempo said —not through a failure of planning, but because, the more frequently they review projects, the sooner they can see a project is failing and drop it, with their surviving projects being more profitable on average.

In the survey report’s conclusion, Tempo states. “The highest-performing teams aren’t clinging to perfect plans or heroic roadmaps. They’re reviewing frequently, creating alignment across teams, reallocating resources without drama, and canceling projects early when the numbers stop adding up.”

Microsoft accelerates pace of VS Code development 13 Mar 2026, 9:27 am

Microsoft is speeding up the delivery of its Visual Studio Code updates. Since last summer, the company has been making monthly releases, each with three or four patches and new functionality, but starting from March 9 the changes will come weekly, it announced on GitHub.

Visual Studio Code is a free source-code editor that is available for Windows, macOS, Linux, and Raspberry Pi OS and comes with support for JavaScript, TypeScript, and Node.js, as well as extensions for a variety of other languages.

The news of the changes has been met with guarded approval from users. Many welcomed the new regularity, although one expressed concern that standards would be slipping. “Will we be trading faster releases for a less stable product, with things thrown in willy-nilly with no testing, and with no way to provide feedback?” asked one user, while another user said that while he liked it personally, he wondered if it meant “having to deal with customers on a much wider range of versions.”

In its last monthly update, Microsoft released Visual Studio Code 1.109, which introduced multiple enhancements for coding agents, including improvements for optimization, extensibility, security, and session management.

Databricks launches Genie Code to automate data science and engineering tasks 13 Mar 2026, 3:01 am

Databricks has launched Genie Code, a new AI agent, to help enterprise data practitioners automate data science and engineering tasks.

Available as a panel inside Databricks’ notebooks, SQL Editor, and Lakeflow Pipelines editor, Genie Code can be used to plan, build, deploy, and maintain end-to-end machine learning (ML) workflows, including automating experiment tracking with MLflow, monitoring pipelines, fixing model issues, and optimizing resources, the company wrote in a blog post.

Analysts say Genie Code can be valuable to enterprises.

“Data teams spend enormous time stitching together pipelines, SQL transformations, feature engineering logic, and orchestration code. Genie Code aims to collapse that work into a conversational interface that can generate and modify those artifacts automatically inside the Databricks environment,” said Dion Hinchcliffe, lead of the CIO practice at The Futurum Group.

That, Hinchcliffe said, will help enterprise data teams shorten the time required to generate insights from data and aid in faster operational decision-making.

Automating governance and compliance

Beyond productivity gains, Genie Code can also reduce the time and effort required to tackle governance and compliance challenges as data pipelines and ML workflows grow more complex and distributed, said Ashish Chaturvedi, executive research leader at HFS Research.

Typically, ensuring that developers consistently follow access controls, policy requirements, and audit standards has traditionally required significant manual oversight, and Genie Code’s automation capabilities, combined, he said, are designed to streamline that process while keeping workflows aligned with enterprise governance frameworks using Databricks’ Unity Catalog.

Automating governance and compliance, according to Pareekh Jain, principal analyst at Pareekh Consulting, solves a major pain point for CIOs.

Genie Code’s extensibility via the Model Context Protocol (MCP) can also be helpful for developers.

Support for MCP will allow developers to integrate Genie Code with third-party tools, such as Jira, GitHub, Confluence, and Notion, and trigger tasks like training models or troubleshooting pipelines directly from the systems they already use, while automatically updating results back to those platforms, Jain said.

This, according to Advait Patel, site reliability engineer at Broadcom, helps reduce context switching: “Instead of jumping between docs, notebooks, dashboards, and troubleshooting screens, they are trying to keep more work inside one assistant.”

Turning the lakehouse into an AI runtime

Some analysts say the launch of Genie Code signifies a broader strategic shift for Databricks rather than the launch of just another developer productivity tool.

Stephanie Walter, practice leader of AI stack at HyperFRAME Research, says Genie Code is a subtle strategy to make the lakehouse a runtime environment for enterprise AI agents or applications.

“Databricks is gradually turning its platform into an environment where agents can reason over data, write code, execute workflows, and evaluate outcomes within a single governed system. If that vision works, the competitive battle shifts from traditional BI tools or notebooks to who controls the layer where enterprise AI systems actually run,” Walter said.

That could be a significant shift for CIOs, according to Hinchcliffe.

“It will move the center of gravity for enterprise development toward the data platform itself. Whichever vendor becomes the ‘AI operating system’ for data engineering and analytics could end up owning a massive portion of the enterprise software stack over the next decade,” Hinchcliffe said.

In fact, Hinchcliffe sees similar strategic moves from Snowflake: “Cortex Code from Snowflake is pursuing a similar goal by helping generate queries, pipelines, and analytics workflows inside the Snowflake ecosystem.”

Jain, too, sees similar advancements with hyperscalers, at least in the form of AI agents managing data workflows: “Microsoft is integrating Fabric Copilot, GitHub Copilot for data, and AI-driven pipelines, Google is building BigQuery AI agents and Gemini data assistants, and AWS offers Q for data analytics and Bedrock agents for pipeline orchestration.”

However, both think that Databricks might have an advantage, especially against Snowflake.

“Where Databricks may have an advantage is platform depth. The Databricks stack spans data engineering, ML workflows, and generative AI tooling under one architecture. This means a coding agent can reach across a broader set of primitives,” Hinchcliffe said.

“Databricks has also been investing heavily in observability and LLMOps capabilities. This matters because enterprises increasingly want to monitor how AI-generated code behaves in production,” Hinchcliffe added. Genie Code has been made generally available and comes at no additional cost to customers, the company said.

Migrating Python to Rust with Claude: What could go wrong? 13 Mar 2026, 2:00 am

Take a wild ride with us, as we use a large language model to convert a Python app to Rust. Also, could Pandas finally compel you to ditch Excel? And, is Python’s native JIT the Python performance booster we’ve all been waiting for? All this and more, in this week’s report.

Top picks for Python readers on InfoWorld

What I learned using Claude Sonnet to migrate Python to Rust

“Let’s rewrite a Python project in Rust with an LLM,” I said. “It’ll be fun,” I said. It was also bumpy, eye-opening, and, yeah, kinda fun, actually.

How to use Pandas for data analysis in Python

Stop staring at spreadsheets and take real control of your data tables. Pandas gives you industrial-strength data tools to wrangle, crunch, and visualize your numbers.

Get started with Python’s new native JIT

Python’s native JIT offers faster code with no rewrites, no new libraries, and just a new version of the Python interpreter. Mileage will vary, but if you’re using Python 3.14, you can try it right away.

More good reads and Python updates elsewhere

PEP 827: Type Manipulation (Proposed)

“We propose adding powerful type-level introspection and construction facilities to Python’s type system.” In short: Make it possible to manipulate Python types in ways that are as powerful and expressive as Python itself. It’s an early-stages proposal, but with broad reach. Expect much discussion (and dissension).

PEP 747: Annotating Type Forms (Accepted)

Another powerful advancement for Python’s type-linting features. Possible use cases include describing in the type system if a given value can be assigned to a specified type or coerced to another type.

Why it took three years and two attempts to get Python’s lazy imports feature

Or: “How to add a huge new feature to a software ecosystem without fracturing it.” Read the backstory for one of Python’s most powerful new features.

The resource-usage implications of removing the GIL

Will multicore builds of Python make workloads faster? Some, but not all. Will they change how much memory and power your system uses regardless of workload? Very likely. (Warning: This paper uses academic language!)

The AI coding hangover 13 Mar 2026, 2:00 am

For the past few years, I’ve watched a specific story sell itself in boardrooms: “Software will soon be free.” The pitch is simple: Large language models can write code, which is the bulk of what developers do. Therefore, enterprises can shed developers, point an LLM at a backlog, and crank out custom business systems at the speed of need. If you believe that pitch, the conclusion is inevitable: The organization that moves fastest to replace people with AI wins.

Today that hopeful ambition is colliding with the reality of how enterprise systems actually work. What’s blowing up isn’t AI coding as a capability. It’s the enterprise decision-making that treats AI as a developer replacement rather than a developer amplifier. LLMs are undeniably useful. But the enterprises that use them as a substitute for engineering judgment are now discovering they didn’t eliminate cost or complexity. They just moved it, multiplied it, and, in many cases, buried it under layers of unmaintainable generated code.

An intoxicating, incomplete story

These decisions aren’t made in a vacuum. Enterprises are encouraged and influenced by some of the loudest voices in the market: AI and cloud CEOs, vendors, influencers, and the internal champions who need a transformative story to justify the next budget shift. The message is blunt: Coders are becoming persona non grata. Prompts are the new programming language. Your AI factory will output production software the way your CI/CD system outputs builds.

That narrative leaves out key details every experienced enterprise architect knows: Software isn’t just typing. The hard parts are requirements without conflict, trustworthy data, security, performance, and operations. Trade-offs demand accountability, and removing humans from design decisions doesn’t eliminate risk. It removes the very people who can detect, explain, and fix problems early.

Code that works until it doesn’t

Here’s the pattern I’ve seen repeated. A team starts by using an LLM for grunt work. That goes well. Then the team uses it to generate modules. That goes even better, at least at first. Then leadership asks the obvious question: If AI can generate modules, why not entire services, entire workflows, entire applications? Soon, you have “mini enterprises” inside the enterprise, empowered to spin up full systems without the friction of architecture reviews, performance engineering, or operational planning. In the moment, it feels like speed. In hindsight, it’s often just unpriced debt.

The uncomfortable fact is that AI-generated code is often inefficient. It usually over-allocates, over-abstracts, duplicates logic, and misses subtle optimization opportunities that experienced engineers learn through pain. It may be “correct” in the narrow sense of producing outputs, but will it meet service-level agreements, handle edge cases, survive upgrades, and operate within cost constraints? Multiply that across dozens of services, and the result is predictable: cloud bills that grow faster than revenue, latency that creeps upward release after release, and temporary workarounds that become permanent dependencies.

Technical debt doesn’t disappear

Traditional technical debt is at least visible to the humans who created it. They remember why a shortcut was taken, what assumptions were made, and what would need to change to unwind it. AI-generated systems create a different kind of debt: debt without authorship. There is no shared memory. There is no consistent style. There is no coherent rationale spanning the codebase. There is only an output that “passed tests” (if tests were even written) and a deployment that “worked” (if observability was even instrumented).

Now add the operational reality. When an enterprise depends on these systems for critical functions such as quoting, billing, supply chain decisions, fraud-detection workflows, claims processing, or regulatory reporting, the stakes become existential. You can’t simply rewrite everything when something breaks. You have to patch, optimize, and secure what exists. But who can do that when the code was generated at scale, stitched together with inconsistent patterns, and refactored by the model itself over dozens of iterations? In many cases, nobody knows where to start because the system was never designed to be understood by humans. It was designed to be produced quickly.

This is how enterprises paint themselves into a corner. They have software that is simultaneously mission-critical and effectively unmaintainable. It runs. It produces value. It also leaks money, accumulates risk, and resists change.

Bills, instability, and security risks

The economic math that justifies shedding developers often assumes the highest cost is payroll. In reality, the highest recurring costs for modern enterprises tend to be operational: cloud compute, storage, data egress, third-party SaaS sprawl, incident response, and the organizational drag created by unreliable systems. When AI-generated code is inefficient, it doesn’t just run slower. It runs more, scales wider, and fails in weird ways that are expensive to diagnose.

Then comes the security and compliance side. Generated code may casually pull in libraries, mishandle secrets, log sensitive data, or implement authentication and authorization patterns that are subtly incorrect. It may create shadow integrations that bypass governance. It may produce infrastructure-as-code changes that work in the moment but violate the enterprise’s long-term platform posture. Security teams can’t keep up with a code factory that outpaces review capacity, especially when the organization has simultaneously reduced the engineering staff that would normally partner with security to build safer defaults.

The enterprise ends up paying for the illusion of speed with higher compute costs, more outages, greater vendor lock-in, and greater risk. The irony is painful: The company reduced the developer headcount to cut costs, then spent the savings, plus more, on cloud resources and firefighting.

The damage is real

A predictable next chapter is unfolding in many organizations. They’re hiring developers back, sometimes quietly, sometimes publicly, and sometimes as platform engineers or AI engineers to avoid admitting that the original workforce strategy was misguided. These returning teams are tasked with the least glamorous work in IT: making the generated systems comprehensible, observable, testable, and cost-efficient. They’re asked to build guardrails that should have existed from day one: coding standards, reference architectures, dependency controls, performance budgets, deployment policies, and data contracts.

But here’s the rub: you can’t always reverse the damage quickly. Once a sprawling, generated system becomes the backbone of revenue operations, you’re constrained by uptime and business continuity demands. Refactoring becomes surgery performed while the patient is running a marathon. The organization can recover, but it often takes far longer than the original AI transformation took to create the mess. And the cost curve is cruel: The longer you wait, the more dependent the business becomes, and the more expensive the remediation becomes.

The oldest lesson in tech

If it seems too good to be true, it usually is. That doesn’t mean AI coding is a dead end. It means the enterprise must stop confusing automation with replacement. AI excels at automating tasks. It is not good at owning outcomes. It can draft code, translate patterns, generate tests, summarize logs, and accelerate routine work. It can help a strong engineer move faster and catch more issues earlier. But it cannot replace human responsibility for architecture, data modeling, performance engineering, security posture, and operational excellence. Those are not typing issues. They are judgment issues.

The enterprises that win in 2026 and beyond won’t be the ones that eliminate developers. They’ll be the enterprises that pair developers with AI tools, invest in platform discipline, and demand measurable quality, maintainability, cost-efficiency, resilience, and security. They’ll treat the model as a power tool, not an employee. And they’ll remember that software is not merely produced; it is stewarded.

Gemini CLI introduces plan mode 12 Mar 2026, 3:53 pm

Google has added a plan mode to Gemini CLI, its open-source software engineering agent that runs on the command line.

With plan mode, announced March 11, Gemini CLI focuses first on analyzing a request, planning complex changes, and understanding the codebase or dependencies in a read-only mode that is safe from accidental changes or executions. Plan mode will also ask questions to clarify goals before proposing a strategy for a user to review. Plan mode is now is enabled by default for all users, according to Google. Users can enter plan mode at any time by typing /plan in the input box, pressing Shift+Tab to cycle through approval modes, or simply asking the agent to “start a plan.”

Plan mode restricts Gemini CLI to a subset of read-only tools such as read_file, grep_search, and glob to validate assumptions, Google said. When active, the agent can navigate a codebase, search for patterns, and read documentation, but it cannot modify any files except for its own internal plans. Users can ask Gemini CLI to “research how to migrate this database” or “plan a new feature,” and dependencies will be mapped out and a solution proposed without risk of eager code changes. A new ask_user tool has been introduced, allowing the agent to pause its research and ask targeted questions to clarify a user’s goals or gather missing information.

JetBrains unveils AI tracing library for Kotlin and Java 12 Mar 2026, 3:21 pm

JetBrains has introduced Tracy, an AI tracing library for the Kotlin and Java languages.

Announced March 11 and accessible from GitHub, Tracy helps developers trace, monitor, and evaluate AI-powered features directly from their Kotlin or Java projects, JetBrains said. The open-source Kotlin library provides a unified API to capture structured traces and helps developers debug failures, measure execution time, and track large language model (LLM) usage across model calls, tool calls, and custom application logic.

Tracy implements the OpenTelemetry Generative AI Semantic Conventions for span attributes and event naming, thus ensuring traces remain compatible with any OpenTelemetry-compliant back end. JetBrains noted the following specific uses for Tracy:

- Tracing AI clients to capture messages, cost, token usage, and execution time.

- Tracing any function to record inputs, outputs, and execution duration.

- Creating and managing spans manually.

- Exporting traces to supported back ends (currently Langfuse and Weave).

Licensed under the Apache 2.0 License, Tracy is compatible with Kotlin from version 2.0.0 and Java from version 17. Integrations can be made with SDKs from OpenAI, Anthropic, and Gemini. The library also works with common Kotlin/LLM stacks including OkHttp and Ktor clients, as well as OpenAI, Anthropic, and Gemini ones, JetBrains said.

Why Postgres® has won as the de facto database: Today and for the agentic future 12 Mar 2026, 11:13 am

The AI economy is projected to reach $17 trillion by 2028, fundamentally altering how organizations architect their infrastructure. Driven by this shift, 95% of major global enterprises are on a mission-critical sprint to become their own AI and data platforms within the next two years.

Yet only 13% of enterprises have successfully found the formula. Their secret to mainstreaming agentic AI? Abandoning fragmented, legacy architectures and placing their data directly alongside their AI in a secure, compliant, and sovereign manner.

As organizations rapidly transition to an “agentic” workforce, they are entering a highly volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) environment. Surviving this shift requires abandoning rigid, traditional strategies in favor of agility and resilience. For enterprises leading the charge, the foundational layer of choice is clear: true open source relational databases. Today, 81% of these successful enterprises have committed to open source strategies, with over 40% standardizing on PostgreSQL as their relational data layer.

As Doug Flora, VP of Product Marketing at EnterpriseDB (EDB), noted: “It’s imperative in moments of rapid change to follow the patterns of the leaders looking to forge success, not the majority who are still working in the patterns of the recent past. Those committing to open source and a mission-critical focus on sovereignty over their AI and data are plotting a pathway to agentic success that achieves 5x the ROI of the majority.”

Extensibility matters: AI needs both structured and unstructured data

AI applications cannot run on vector embeddings alone; they require a deep synthesis of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data. Unlike many legacy databases that bolt on new features as afterthoughts, Postgres was natively architected for core extensibility. It empowers developers to extend data types, indexes, query planners, functions, and storage engines dynamically.

By unifying vectorized data with traditional transactional (binary) data, Postgres effectively gives AI agents the “eyes, ears, and brain” necessary to sense inputs and operate autonomously within a single, ACID-compliant environment.

An ecosystem built for architectural agility

In a rapidly expanding data ecosystem, relying on a fragmented architecture of specialized databases creates complex synaptic connectors prone to latency, integration failures, and data silos—or what amounts to human hallucinations at the system level. Postgres eliminates this technical debt by extending a single database engine to meet diverse workload demands.

“Developers have long loved Postgres for its extensibility, flexibility, and open innovation model. Now global enterprises are recognizing that same value, making Postgres a strategic decision and running mission-critical data systems on it,” said Jozef de Vries, SVP, Core Database Engineering, EDB.

Developers can seamlessly extend Postgres to handle highly complex, volatile workloads:

- pgvector: Enables advanced vector search, allowing developers to combine relational data, metadata, and embeddings to build robust retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) applications

- Citus: Accelerates multi-tenant SaaS applications and powers real-time analytics (HTAP) via transparent sharding and parallel query execution

- PostGIS: Delivers enterprise-grade geospatial querying, critical for defense and retail industries

- TimescaleDB: Manages massive time-series data crucial for complex analytic models and agentic learning patterns

- pgraph: Handles complex, interconnected data traversals to uncover hidden relationships

The future needs crowdsourced intelligence, not vendor lock-in

Crucially, no single corporate entity owns Postgres. Its vitality relies on the collective intelligence of one of the largest independent developer communities on the planet. In 2025 alone, more than 260 developers contributed code directly to PostgreSQL’s core database engine, with hundreds more participating in testing, reviews, and documentation across the world. Beyond the codebase, the ecosystem is supported by hundreds of user groups, meetups, and international PostgreSQL conferences that keep innovation flowing across all five continents.

While enterprise-grade platforms are built around Postgres to optimize it for sovereign, agentic environments—with big tech giants among the top commercial contributors and EDB leading with more than 30% of contributions—its innovation comes directly from this rich and diverse community that continues to expand. Drawing on the principles of James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds, this crowdsourced intelligence ensures that the database evolves faster and more robustly than it would in any proprietary, single-vendor ecosystem.

Securing a sovereign data future

To thrive in the agentic future, engineering and data leaders must make two critical architectural moves: First, break free from locked-in legacy relational ecosystems, such as Oracle, MySQL, SQL Server, or Greenplum , that constrain agility.

Second, harness the immense extensibility of Postgres, its vibrant open source community, and its core ACID capabilities to unify data and AI.

The future of enterprise architecture isn’t about renting space in a hyperscaler’s proprietary ecosystem. It’s about creating your own sovereign platform, where your structured and unstructured data seamlessly power a new agentic workforce under your complete control. Move your data to Postgres now, or risk missing the foundation of the agentic future.

Get your complimentary copy of the O’Reilly book Building a Data and AI Platform with PostgreSQL.

Running agents with Amazon Bedrock AgentCore 12 Mar 2026, 2:00 am

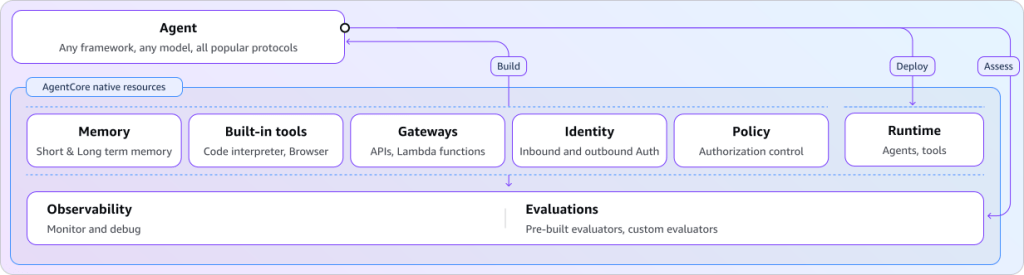

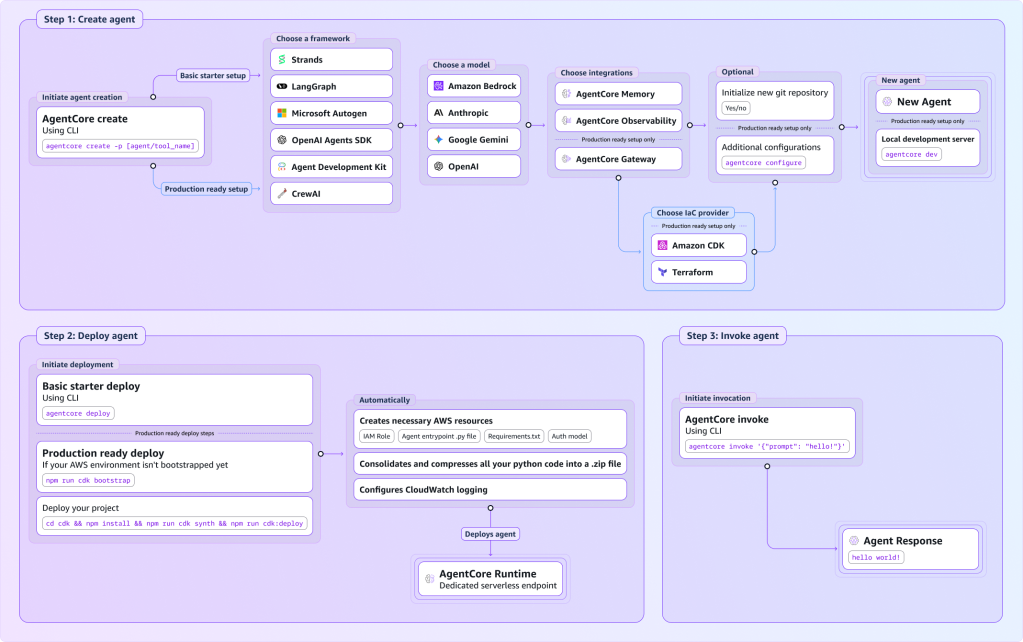

While Amazon Bedrock helps you build and scale generative AI applications, Amazon Bedrock AgentCore provides an enterprise-grade infrastructure and operations layer for deploying and managing AI agents at scale. AgentCore itself is completely agnostic about models, frameworks, and integrations, although its starter kit CLI only supports the most prominent of these.

That CLI can generate agents using Amazon Bedrock, Anthropic, Google Gemini, and OpenAI models, using Strands, LangGraph, Microsoft Autogen, OpenAI Agents SDK, Google Agent Development Kit, and CrewAI frameworks, and using Amazon AgentCore Memory, AgentCore Observability, and AgentCore Gateway integrations. Note that many of these are produced by competitors to AWS.

AgentCore’s core services include a runtime, memory (both short-term and long-term), a gateway, identity management, a sandboxed code interpreter, a cloud-based browser, observability, an evaluation service, and a policy capability that runs outside the agent. We’ll discuss these in more detail below.

Direct cloud platform competitors to AgentCore provide similar enterprise-level hosting, security, and governance for agents within their respective ecosystems. They include:

- Google Cloud Agent SDK (ADK): Built on Vertex AI, the ADK offers deep integration with Gemini models.

- Azure AI Foundry Agents: Best for those heavily invested in the Microsoft ecosystem and Azure OpenAI Service.

- Databricks Agent Bricks: A data-centric alternative that uses the Unity Catalog to build agents directly from enterprise data.

Additional competitors (and sometimes collaborators) to AgentCore include the OpenAI Agents SDK, LangChain/LangGraph, CrewAI, and SmythOS.

Amazon Bedrock AgentCore overview chart.

Amazon Web Services

AgentCore quick start CLI workflow. The three steps are agent creation, agent deployment, and agent invocation.

Amazon Web Services

AgentCore Core Services

AgentCore Core Services include runtime, memory (both short-term and long-term), a gateway, identity management, a sandboxed code interpreter, a cloud-based browser, observability, an evaluation service, and a policy capability that runs outside the agent. You can use whichever of these services that are useful to support your agent development.

AgentCore Runtime is a secure, serverless runtime environment for deploying and scaling dynamic AI agents and tools. It provides fast cold starts for real-time interactions, extended runtime support for asynchronous agents, true session isolation, built-in identity, and support for multi-modal and multi-agent agentic workloads. The runtime integrates with custom frameworks and any open-source framework as well as any foundation model in or outside of Amazon Bedrock.

AgentCore Memory lets you build context-aware agents with control over what the agent remembers and learns. It has support for both short-term memory for multi-turn conversations, and long-term memory that persists across sessions. It can share memory stores across agents, and it can learn from experiences. It works with LangGraph, LangChain, Strands, and LlamaIndex.

AgentCore Gateway is a secure way to convert any APIs, Lambda functions, and existing services into Model Context Protocol (MCP)-compatible tools. It can also connect to pre-existing MCP servers, making them available to AI agents through gateway endpoints with a few lines of code.

AgentCore Identity is a secure, scalable agent identity, access, and authentication management service. It is compatible with identity and credential providers, eliminating the need for user migration or rebuilding authentication flows.

AgentCore Code Interpreter is an isolated sandbox environment for agents to execute code, enhancing their accuracy and scope. It supports Python, JavaScript, and TypeScript. It provides support for a default execution time of 15 minutes, which can be extended to up to eight hours. A best practice is to keep code snippets concise and focused on specific tasks. You can use the Strands Agents SDK with Python or TypeScript, or either the bedrock_agentcore SDK or Boto3 with Python. The session isolation architecture for the code interpreter and the browser uses Firecracker microVMs.

AgentCore Browser is a remote browser that runs in a separate environment rather than on the local machine. For agent development, remote browsers allow AI agents to interact with the web as humans do. AgentCore Browser allows your agent and model to navigate websites, fill forms, click buttons, and parse dynamic content, and allows you to monitor a live view and intervene if necessary. AgentCore Browser integrates with Nova Act, Strands, and Playwright to automate web interactions.

AgentCore Observability is a unified view to trace, debug, and monitor agent performance in production, which offers detailed visualizations of each step in the agent workflow, enabling you to inspect an agent’s execution path, audit intermediate outputs, and debug performance bottlenecks and failures. It integrates with any observability stack that supports OpenTelemetry (OTEL) format.

AgentCore Evaluations is a service for automated, consistent, and data-driven agent assessment. AgentCore Evaluations measures how well your agents and tools execute tasks, handle edge cases, and maintain output reliability across diverse inputs and contexts.

AgentCore Policy is a capability that provides deterministic control to ensure agents operate within defined boundaries and business rules without slowing them down. You can author rules using natural language or Cedar (AWS’s open-source policy language). Policy runs outside the agents so that the models can’t violate the constraints.

AgentCore use cases

Amazon Bedrock AgentCore lets you deploy AI agents with scale, reliability, and security. There are three major categories of use cases for AgentCore: agents, MCP servers, and agent platforms.

With agents, you can build AI apps that reason, use tools, and maintain context. You can apply these to customer support, workflow automation, data analysis, or coding assistance, for example. Using AgentCore, your agents run serverlessly, with isolated sessions, persistent memory, and built-in observability.

AgentCore helps you convert APIs, databases, and services into tools that MCP-compatible agents can use. You can deploy a gateway that wraps your Lambda functions or OpenAPI specs and makes your back end accessible to agents, without rewriting code.

Finally, you can build agent platforms that help your developers or customers deploy agents using approved tools, shared memory stores, and governed access to enterprise services. You can include observability, authentication, and compliance using standard AgentCore core services.

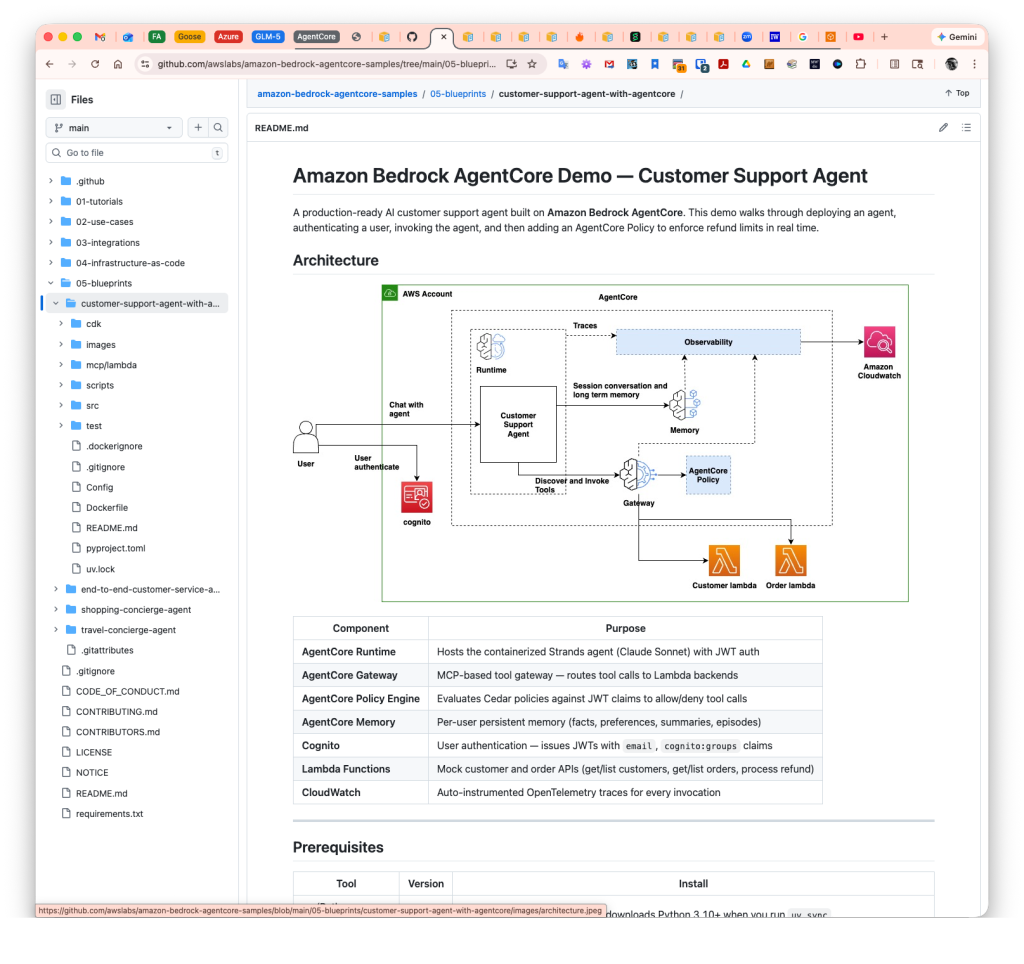

Customer support agent example

The AgentCore team suggested that I try the Customer Support Agent demo (see architecture diagram below). While it looked like a typical AWS architecture with multiple services involved, I’ve seen much worse. What the heck, I thought.

Amazon Bedrock AgentCore Demo – Customer Support Agent. This demo shows how to deploy an agent, authenticate a user, invoke the agent, and then add an AgentCore Policy to enforce refund limits in real time. It’s essentially the same application as the CLI-based Get Started with Amazon Bedrock AgentCore Demo, although there’s more documentation and you can read the code before trying it.

Amazon Web Services

Almost a week later, with multiple bugs and other roadblocks reported and fixed, I finally completed the exercise. The terminal logs follow, starting with the deployment script. I’ve skipped over showing you the step of logging into AWS from my local command line, since it bounces to a web page and back, in order to connect the local session to the proper credentials.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % scripts/deploy.sh

==> Pre-flight checks

Verifying Bedrock model access (global.anthropic.claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929-v1:0)...

WARNING: Could not invoke Bedrock model (global.anthropic.claude-sonnet-4-5-20250929-v1:0).

Possible reasons:

1. Anthropic first-time usage form not completed.

Complete it in the Bedrock console Playground by selecting any Anthropic Claude model.

Details: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/simplified-amazon-bedrock-model-access/

2. Your current IAM identity lacks bedrock:InvokeModel permission.

Note: the deployed agent uses its own execution role, so this may not

be a problem. Verify after deployment with: uv run agentcore invoke

The deploy will continue.

All checks passed.

==> Installing Python dependencies (uv sync)

Resolved 110 packages in 14ms

Audited 103 packages in 11ms

==> Installing CDK dependencies (npm install)

up to date, audited 337 packages in 901ms

37 packages are looking for funding

run `npm fund` for details

3 vulnerabilities (1 moderate, 2 high)

To address all issues, run:

npm audit fix

Run `npm audit` for details.

==> Bootstrapping CDK (if needed)

> cdk@0.1.0 cdk

> cdk bootstrap

⏳ Bootstrapping environment aws://577405208411/us-east-2...

Trusted accounts for deployment: (none)

Trusted accounts for lookup: (none)

Using default execution policy of 'arn:aws:iam::aws:policy/AdministratorAccess'. Pass '--cloudformation-execution-policies' to customize.

✅ Environment aws://577405208411/us-east-2 bootstrapped (no changes).

NOTICES (What's this? https://github.com/aws/aws-cdk/wiki/CLI-Notices)

37013 (cli) cdk watch triggers deployment unexpectedly or not at all

Overview: Do not use 'cdk watch' with this version of the cdk cli.

Upgrade to ^2.1106.0.

Affected versions: cli: >=2.1103.0 =2.1100.0 ". For example, "cdk acknowledge 37013".

==> Deploying all stacks

> cdk@0.1.0 cdk:deploy:ci

> cdk deploy --all --require-approval never --outputs-file /Volumes/Glauce/repos/amazon-bedrock-agentcore-samples/05-blueprints/customer-support-agent-with-agentcore/cdk-outputs.json

✨ Synthesis time: 2.29s

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: start: Building supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack Template

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: success: Built supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack Template

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: start: Building supportAgentDemo-AppImage

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: start: Publishing supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack Template (current_account-current_region-f5e9391a)

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: success: Published supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack Template (current_account-current_region-f5e9391a)

#0 building with "desktop-linux" instance using docker driver

#1 [internal] load build definition from Dockerfile

#1 transferring dockerfile: 795B done

#1 DONE 0.0s

#2 [internal] load metadata for ghcr.io/astral-sh/uv:python3.13-bookworm-slim

#2 DONE 3.6s

#3 [internal] load .dockerignore

#3 transferring context: 814B done

#3 DONE 0.0s

#4 [1/7] FROM ghcr.io/astral-sh/uv:python3.13-bookworm-slim@sha256:531f855bda2c73cd6ef67d56b733b357cea384185b3022bd09f05e002cd144ca

#4 DONE 0.0s

#5 [internal] load build context

#5 transferring context: 1.87MB 0.0s done

#5 DONE 0.0s

#6 [5/7] RUN uv pip install aws-opentelemetry-distro==0.12.2

#6 CACHED

#7 [4/7] RUN uv pip install -r pyproject.toml

#7 CACHED

#8 [2/7] WORKDIR /app

#8 CACHED

#9 [3/7] COPY pyproject.toml pyproject.toml

#9 CACHED

#10 [6/7] RUN useradd -m -u 1000 bedrock_agentcore

#10 CACHED

#11 [7/7] COPY . .

#11 DONE 0.0s

#12 exporting to image

#12 exporting layers done

#12 writing image sha256:103477e07cdce77a6d41dc7f875d781cb408dc59556cdf205c5dddeed5cc50d0 done

#12 naming to docker.io/library/cdkasset-9d592d01e5467aa35239774fad1da2f13bc79a6fdfad62b7b89146b9d8f12462 done

#12 DONE 0.0s

View build details: docker-desktop://dashboard/build/desktop-linux/desktop-linux/jogcv8dnbz67ymx5fi5dnrfbt

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: success: Built supportAgentDemo-AppImage

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: start: Publishing supportAgentDemo-AppImage (current_account-current_region-eadbec27)

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack: start: Building supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack Template

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack: success: Built supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack Template

The push refers to repository [577405208411.dkr.ecr.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/cdk-hnb659fds-container-assets-577405208411-us-east-2]

f75c8a00d29b: Preparing

e9cefea56108: Preparing

6ad1a9eaa547: Preparing

2c4f33ca63a0: Preparing

bd07e5776977: Preparing

65d80ab29699: Preparing

d700e87997ad: Preparing

b27347ec89d2: Preparing

733eb94a487b: Preparing

dac1af1d7cd9: Preparing

bd390c400455: Preparing

d700e87997ad: Waiting

b27347ec89d2: Waiting

733eb94a487b: Waiting

dac1af1d7cd9: Waiting

bd390c400455: Waiting

65d80ab29699: Waiting

e9cefea56108: Layer already exists

6ad1a9eaa547: Layer already exists

2c4f33ca63a0: Layer already exists

bd07e5776977: Layer already exists

65d80ab29699: Layer already exists

d700e87997ad: Layer already exists

733eb94a487b: Layer already exists

b27347ec89d2: Layer already exists

dac1af1d7cd9: Layer already exists

bd390c400455: Layer already exists

f75c8a00d29b: Pushed

9d592d01e5467aa35239774fad1da2f13bc79a6fdfad62b7b89146b9d8f12462: digest: sha256:455ae21c8896a1df8558466d99b87e0f038e79b5baaf00514f810f95183562d0 size: 2627

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: success: Published supportAgentDemo-AppImage (current_account-current_region-eadbec27)

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: deploying... [1/2]

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack: creating CloudFormation changeset...

✅ supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack

✨ Deployment time: 13.06s

Outputs:

supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack.ImageUri = 577405208411.dkr.ecr.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/cdk-hnb659fds-container-assets-577405208411-us-east-2:9d592d01e5467aa35239774fad1da2f13bc79a6fdfad62b7b89146b9d8f12462

Stack ARN:

arn:aws:cloudformation:us-east-2:577405208411:stack/supportAgentDemo-DockerImageStack/6d08ccf0-1664-11f1-8de3-0a00ca3e2d9f

✨ Total time: 15.35s

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack: start: Publishing supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack Template (current_account-current_region-8aa3c459)

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack: success: Published supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack Template (current_account-current_region-8aa3c459)

✅ supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack

✨ Deployment time: 39.12s

Outputs:

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.AccountId = 577405208411

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.AuthorizerDiscoveryUrl = https://cognito-idp.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/us-east-2_NaZm7AOfz/.well-known/openid-configuration

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.ClientId = 7nvmhkv45gh933mircjoji1gfe

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.CognitoDomain = supportagentdemo-577405208411-us-east-2.auth.us-east-2.amazoncognito.com

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.GatewayId = supportagentdemo-gateway-7d3m0sdfzy

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.GatewayUrl = https://supportagentdemo-gateway-7d3m0sdfzy.gateway.bedrock-agentcore.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/mcp

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.MemoryArn = arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:memory/supportAgentDemo_Memory_v2-bLfMFAGQmp

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.MemoryId = supportAgentDemo_Memory_v2-bLfMFAGQmp

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.Region = us-east-2

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.RuntimeArn = arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.RuntimeId = supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.RuntimeName = supportAgentDemo_Agent

supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack.UserPoolId = us-east-2_NaZm7AOfz

Stack ARN:

arn:aws:cloudformation:us-east-2:577405208411:stack/supportAgentDemo-AgentCoreStack/74e9b510-1664-11f1-8ec7-0606ac99759d

✨ Total time: 41.4s

NOTICES (What's this? https://github.com/aws/aws-cdk/wiki/CLI-Notices)

37013 (cli) cdk watch triggers deployment unexpectedly or not at all

Overview: Do not use 'cdk watch' with this version of the cdk cli.

Upgrade to ^2.1106.0.

Affected versions: cli: >=2.1103.0 =2.1100.0 ". For example, "cdk acknowledge 37013".

CDK outputs written to /Volumes/Glauce/repos/amazon-bedrock-agentcore-samples/05-blueprints/customer-support-agent-with-agentcore/cdk-outputs.json

==> Generating .bedrock_agentcore.yaml

Generated /Volumes/Glauce/repos/amazon-bedrock-agentcore-samples/05-blueprints/customer-support-agent-with-agentcore/.bedrock_agentcore.yaml

============================================================

Deployment complete!

============================================================

Next steps:

1. Check agent status:

uv run agentcore status

2. Create a Cognito user:

uv run scripts/cognito-user.py --create

3. Log in and set your bearer token:

eval $(uv run scripts/cognito-user.py --login --export)

4. Invoke the agent:

uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "Who am I?"}'

To tear down all resources later:

scripts/teardown.sh

The deployment threw some warnings. It turned out that some of the checks weren’t quite reliable. I would fix a problem called out by the script, and it would still be called out the next time I ran it.

Note that part of what the setup script did was to create a Docker pod on my machine and register it with AWS’s directory. When I re-ran the script, it would build new Docker images, so I’d have to delete the old ones manually.

I’ve skipped showing you the agent status script (1 above). It originally didn’t have the uv run prefix, and agentcore, which only existed inside a Python environment, wasn’t found. Once we got that sorted, it gave a false negative the first few times I ran it, until the AWS engineers fixed a parsing problem; then it just worked.

In the user creation script, you also need the uv run prefix:

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run scripts/cognito-user.py --create

Choose a demo user:

1) john@example.com (John Doe)

2) jane@example.com (Jane Smith)

Enter 1 or 2: 1

Password requirements:

- At least 8 characters

- At least one uppercase letter (A-Z)

- At least one lowercase letter (a-z)

- At least one number (0-9)

- At least one special character (e.g. !@#$%^&*)

Password:

User already exists: john@example.com

Password set for: john@example.com

Added to group: standard

User ready. Login with:

eval $(uv run scripts/cognito-user.py --login --export)

The Cognito user has to match a pre-populated database of demo users, which is why there are only two choices.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % eval $(uv run scripts/cognito-user.py --login --export)

Opening browser for authentication...

Waiting for callback...

Login successful. BEDROCK_AGENTCORE_BEARER_TOKEN is now set.

That Cognito login step retrieves the OAuth bearer token to be used for the rest of the session. It expires after an hour. Don’t ask me how I know. Yes, you have to log into AWS as well as logging into Cognito. As AWS explains, the dual login is by design to maintain integrity of the agents developers are building. Cognito identifies who the user is (OAuth bearer token, one-hour expiry), and AWS identifies which service boundary you’re in.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "Who am I?"}'

Using bearer token for OAuth authentication

Using JWT authentication

I'll look up your account information using your email address.Hello! You are **John Doe** (Customer ID: CUST-001). Your account is registered with the email john@example.com, and you've been a member since June 1, 2023. How can I help you today?

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── supportAgentDemo_Agent ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Session: 74d74b58-aa7d-4b8b-9515-e0931743ce1d │

│ ARN: arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf │

│ Logs: aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --follow │

│ aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --since 1h │

│ GenAI Dashboard: https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudwatch/home?region=us-east-2#gen-ai-observability/agent-core │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

That actually went through the Claude model. If you get an error at this point, you might not have Anthropic permission or any Bedrock Claude quota. Asking for a quota is a matter of filling out an AWS form and waiting a couple of days. The next query, for an order list, also goes through the model.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "Show me my recent orders"}'

Using bearer token for OAuth authentication

Using JWT authentication

I'll look up your recent orders for you.Now let me get the full details for each of these orders to show you what items were in them.Here are your recent orders:

**1. Order ORD-12430** - Ordered Feb 5, 2025 | Delivered Feb 10, 2025

- 4K Monitor (1x) - $399.00

- **Total: $399.00** | Status: ✓ Delivered

**2. Order ORD-12420** - Ordered Feb 1, 2025 | Delivered Feb 4, 2025

- Phone Case (1x) - $29.99

- **Total: $29.99** | Status: ✓ Delivered

**3. Order ORD-12410** - Ordered Jan 25, 2025 | Delivered Jan 29, 2025

- Mechanical Keyboard (1x) - $149.99

- **Total: $149.99** | Status: ✓ Delivered

**4. Order ORD-12400** - Ordered Jan 20, 2025 | Delivered Jan 23, 2025

- USB-C Charging Cable (2x) - $12.99 each

- **Total: $25.98** | Status: ✓ Delivered

**5. Order ORD-12345** - Ordered Jan 15, 2025 | Delivered Jan 20, 2025

- Wireless Headphones (1x) - $79.99

- **Total: $79.99** | Status: ✓ Delivered

**6. Order ORD-12300** - Ordered Jan 2, 2025 | Delivered Jan 8, 2025

- Running Shoes (1x) - $249.00

- **Total: $249.00** | Status: ✓ Delivered

All of your recent orders have been delivered successfully! Is there anything specific you'd like to know about any of these orders?

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── supportAgentDemo_Agent ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Session: 74d74b58-aa7d-4b8b-9515-e0931743ce1d │

│ ARN: arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf │

│ Logs: aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --follow │

│ aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --since 1h │

│ GenAI Dashboard: https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudwatch/home?region=us-east-2#gen-ai-observability/agent-core │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

The next query demonstrates that we can ask the customer support agent for refund. This is a small item, so it’s supposed to go through without an issue.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "I need a refund for order ORD-12420. The phone case was damaged."}'

Using bearer token for OAuth authentication

Using JWT authentication

I'll process a refund for your damaged phone case from order ORD-12420.Perfect! Your refund has been processed successfully.

**Refund Details:**

- Refund ID: REF-DC32B

- Order: ORD-12420 (Phone Case)

- Amount: $29.99

- Reason: Damaged item

- Status: Processed

You should receive the refund in your original payment method within **3-5 business days**.

I'm sorry to hear the phone case arrived damaged. Is there anything else I can help you with today?

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── supportAgentDemo_Agent ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Session: 74d74b58-aa7d-4b8b-9515-e0931743ce1d │

│ ARN: arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf │

│ Logs: aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --follow │

│ aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --since 1h │

│ GenAI Dashboard: https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudwatch/home?region=us-east-2#gen-ai-observability/agent-core │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

This next refund request really should be rejected or bumped up to a human customer support agent for approval.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "I need a refund of $399 for order ORD-12430. The monitor has dead pixels."}'

Using bearer token for OAuth authentication

Using JWT authentication

I'll process a refund for your 4K Monitor from order ORD-12430 due to the dead pixels.Your refund has been successfully processed!

**Refund Details:**

- Refund ID: REF-5DEA4

- Order: ORD-12430 (4K Monitor)

- Amount: $399.00

- Reason: Damaged item (dead pixels)

- Status: Processed

You should receive the refund to your original payment method within **3-5 business days**.

I'm sorry the monitor had dead pixels. If you'd like to order a replacement, please let me know and I can assist you with that. Is there anything else I can help you with?

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── supportAgentDemo_Agent ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Session: 74d74b58-aa7d-4b8b-9515-e0931743ce1d │

│ ARN: arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf │

│ Logs: aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --follow │

│ aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --since 1h │

│ GenAI Dashboard: https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudwatch/home?region=us-east-2#gen-ai-observability/agent-core │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

It went through, however. The fix for that (part of the demo, not a bug) is to add some policies.

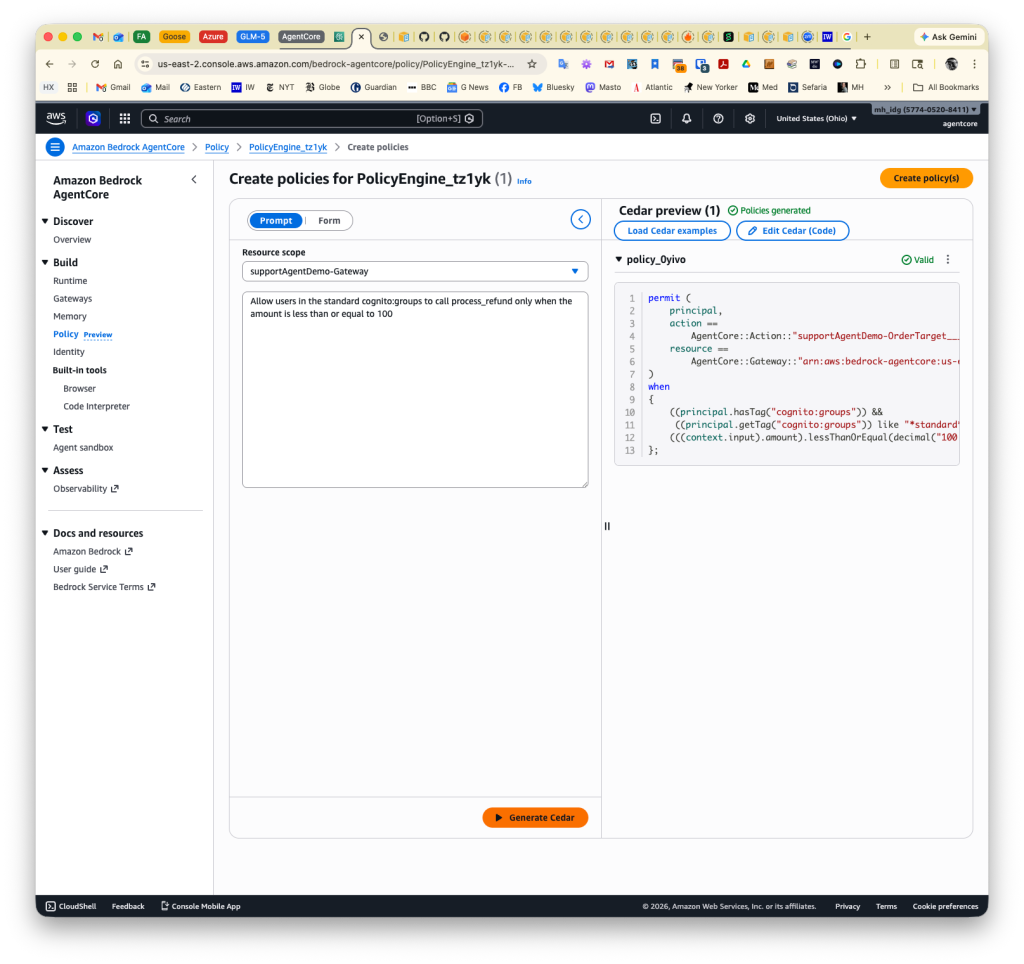

This is the policy that keeps the model from processing refunds >$100. I entered the English prompt at the left; Bedrock generated the Cedar policy at the right.

Amazon Web Services

With the policy in place, I tried again, and the request was denied.

martinheller@Mac customer-support-agent-with-agentcore % uv run agentcore invoke '{"prompt": "I need a full refund for order ORD-12300. The shoes dont fit."}'

Using bearer token for OAuth authentication

Using JWT authentication

I'll process a refund for your Running Shoes from order ORD-12300.I'm unable to process this refund request. The system has denied the refund with the following message:

**"Tool call not allowed due to policy enforcement [No policy applies to the request (denied by default).]"**

This appears to be a policy restriction. Given that order ORD-12300 was delivered on January 8, 2025 (over a month ago), it may be outside the refund window for non-defective items or there may be specific policies regarding fit-related returns.

I recommend:

1. Checking our return policy for the timeframe allowed for returns

2. Contacting our returns department directly for assistance with this older order

3. Inquiring about exchange options if available

I apologize for the inconvenience. Is there anything else I can help you with today?

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────────── supportAgentDemo_Agent ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Session: 74d74b58-aa7d-4b8b-9515-e0931743ce1d │

│ ARN: arn:aws:bedrock-agentcore:us-east-2:577405208411:runtime/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf │

│ Logs: aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --follow │

│ aws logs tail /aws/bedrock-agentcore/runtimes/supportAgentDemo_Agent-U90VrdH6Rf-DEFAULT --log-stream-name-prefix │

│ "2026/03/02/[runtime-logs]" --since 1h │

│ GenAI Dashboard: https://console.aws.amazon.com/cloudwatch/home?region=us-east-2#gen-ai-observability/agent-core │

╰────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

The policy, which is applied outside the agent, worked as designed, but the model was confused as to why. Claude being Claude, it hallucinated some reasons why, and made three irrelevant recommendations. You would think that the model should know about any policies in place, but applying them outside the model avoids the possibility of a malicious prompt convincing the model to issue a large refund. If there’s a safe way to fix that, it’s above my pay grade.

By the way, even with all my retries, running this demo cost me a whopping $0.35 in AWS charges.

A solid foundation for agents

Amazon Bedrock AgentCore is a credible attempt to put together an enterprise-grade infrastructure and operations layer for deploying and managing AI agents at scale. The services themselves seem solid. The example I tried had multiple bugs and documentation errors, but I reported these and the AWS engineers fixed them quickly.

I still question the design of the policy module with respect to how it interacts with the model. There should be a way to pass the reason why an action is denied back to the model so that it doesn’t hallucinate its own reason. I just don’t know how that would work in this architecture.

Cost

Depends on consumption. See https://aws.amazon.com/bedrock/agentcore/pricing/; scroll down to the pricing table and pricing examples.

Platform

Server: AWS. Client: macOS, Linux, or Windows.

Pros

- Strong collection of relevant service modules

- Extensive samples

Cons

- Documentation can be disorienting with multiple options

- The samples seem to be on their “shakedown cruise” at this point

What’s missing from AI-assisted software development 12 Mar 2026, 2:00 am

AI has made writing code feel like cheating. The real trouble shows up right after git push. That is the part almost no one is talking about, and it is where most AI-assisted projects quietly die.

It is not usually the code that fails. It is everything around it, because the cloud is unforgiving.

Developers still run into the same problems they faced before large language models (LLMs) arrived. Environments drift apart. Permissions break in unpredictable ways. Networking works in staging but collapses under real traffic. Rollouts fail and rollbacks do not do what they claim. Monitoring and incident response get set up only after the first outage. These are not exotic issues, but ordinary headaches of shipping software, and they remain stubbornly hard even as code generation becomes trivial.

If we want AI-assisted development to actually scale, we have to confront the real bottlenecks. Everyone feels where the choke point is in the modern agentic software development life cycle, but we do not talk about it nearly enough. We have seen an explosion of coding agents, and many of them are genuinely impressive. But almost no one has tackled the crucial part that kills most AI-generated software: getting it running, safely, in the cloud.

This does not require LLMs to become flawless reasoners, because most platform engineering is not based on some deep logic. It is pattern matching, enforcing boundaries, and checking state. And unlike writing code, configuring infrastructure has fewer degrees of freedom. The space of valid actions is smaller, and the failure modes are well known. With structure, guardrails, and visibility into the real system, today’s models can already be more reliable here than in code generation.

The breakthrough is not better models. It is designing the right system around them.

The new imbalance

The shift happened fast. Developers used to spend weeks writing a new service. Now, a model can generate one in a matter of minutes. The limiting factor is no longer building features but running them.

Deployment is fundamentally different from coding. Writing code is a text problem. Deploying code is a state problem. To deploy safely, a system needs an accurate view of the resources that exist, the relationships between them, and their live configuration. It requires guardrails, reconciliation, and visibility into dependencies that change over time.

LLMs do not have any of that context. They do not know what is already deployed, which permissions are in place, or how different services interact. They operate inside a text box while the cloud is a living system. Asking a model to manipulate that system without giving it structure or guardrails is a recipe for breakage.

Because of this, deploying AI-generated code is actually harder than deploying human-written code. You are no longer dealing with a single developer who understands the system. You are dealing with a generator that outputs large amounts of code but has no understanding of the environment it is meant to run in.

What’s being overlooked

There is a popular narrative that cloud complexity only matters once a company becomes large. In reality, most small applications fail long before scale becomes an issue, and for reasons that have nothing to do with sophisticated infrastructure. The common failure points look almost embarrassingly simple.

Teams often ship:

- Services without proper retries or timeouts

- Functions that are not idempotent and explode on retry

- Migration scripts that fail on the second deploy

- Health checks that do not actually check anything

- Environment variables that differ across machines

- Staging and production resources that accidentally overlap

- Monitoring added only after something goes down

- Continuous integration (CI) pipelines that miss infrastructure regressions

- Rollbacks that do not recreate a working state

These are very common issues. And they’re the exact areas where AI doesn’t really help you yet. AI is great at generating code, but it has no intuition for the messy, boring parts that keep systems alive.

Because writing code is now so fast, teams often spin up more services than they can realistically look after. Not because they lack talent, but because the pace of generation doesn’t match the pace of operational discipline.

The cloud is still a hostile environment for AI

Many people assume that LLMs should be able to automate infrastructure the same way they automate code. But cloud environments have almost none of the qualities that help code generation produce apps that run reliably. Programming languages have grammar, rules, and predictable outcomes. Cloud platforms are inconsistent, fragmented, and in constant motion.

A real-world system is rarely a single configuration language. It is Terraform combined with CLI commands, hand-edited YAML, a CI workflow written years ago, and a set of manual patches someone applied during an incident at 2 am. There is no single source of truth and no stable abstraction for the model to learn from.

LLMs are trained on historical snapshots. Cloud environments are living systems where the same command can behave differently depending on timing, region, service limits, or partial state. Without visibility and structure, AI agents will keep producing infrastructure that only looks valid on paper, yet fails when pushed to the cloud.

The true bottleneck is now operational, not creative

The industry keeps waiting for a better model to arrive and solve everything. But the limiting factor is no longer the intelligence of the model. It is the environment we are asking that model to interact with.

Cloud infrastructure was designed for humans with deep knowledge, tribal context, and plenty of manual control. It was not built for agents that need clean structure, safety constraints, and predictable patterns.

If AI-assisted development is going to scale beyond prototypes, the underlying platform needs to adapt. What models need is not more IQ but better surroundings: environments where state is explicit, destructive actions are constrained, and configuration is represented as structured primitives instead of loosely related text files and scripts.

This is not simply a call for a single magical agent that behaves like an AI platform engineer. It is a call for a cloud that is compatible with AI. Without that shift, the gap between generation and deployment will keep widening.

When deployment stops being the bottleneck

Once the operational side catches up, the impact will be even larger than what we saw when LLMs first made coding accessible. People who were never able to build software will be able to not only assemble apps for demos but also ship them reliably.

That is the real productivity curve AI has not unlocked yet. The coding part is already here. The operational part is where everything slows down. To make AI-assisted development work at scale, we need platforms that give models structure, visibility, and enforce safe boundaries. Once that happens, the cloud stops getting in the way and AI can finally deliver on the promise everyone keeps talking about.

—

New Tech Forum provides a venue for technology leaders—including vendors and other outside contributors—to explore and discuss emerging enterprise technology in unprecedented depth and breadth. The selection is subjective, based on our pick of the technologies we believe to be important and of greatest interest to InfoWorld readers. InfoWorld does not accept marketing collateral for publication and reserves the right to edit all contributed content. Send all inquiries to doug_dineley@foundryco.com.

Nvidia launches Nemotron 3 Super to power enterprise AI agents 12 Mar 2026, 1:40 am

Nvidia has introduced a new reasoning-focused AI model that combines multiple neural network architectures in a bid to improve how enterprise systems handle complex tasks and automation.

The company said its Nemotron 3 Super model combines Mamba sequence modeling, transformer attention, and Mixture-of-Experts routing to support so-called “agentic” AI systems that can plan and execute multi-step workflows across enterprise applications.

[ Related: More Nvidia news and insights ]

In a statement, Nvidia said multi-agent systems can generate up to 15 times more tokens than standard chat interactions. This can lead to “context explosion,” which may cause agents to drift from the original goal and raise costs, as large reasoning models are used for each subtask.

“We are releasing Nemotron 3 Super to address these limitations,” Nvidia said. “The new Super model is a 120B total, 12B active-parameter model that delivers maximum compute efficiency and accuracy for complex multi-agent applications such as software development and cybersecurity triaging.”

Nvidia said the model is released with open weights, datasets, and training recipes, allowing developers to modify it and deploy it on their own infrastructure.

The release reflects a broader shift in the AI industry as vendors move beyond chatbots toward models designed to power autonomous AI agents.

“Enhanced reasoning directly supports better task planning, error correction, and workflow decomposition, which collectively increase the reliability of AI agents for enterprise use,” said Jaishiv Prakash, director analyst at Gartner. “However, the success of agentic systems will not just depend on model capability but on the overall system architecture, including orchestration, data integration, context management, and governance.”

Architecture for enterprise efficiency

Nemotron 3 Super reflects Nvidia’s push to improve performance for enterprise AI workloads that involve sustained reasoning and long-context processing. The model’s hybrid architecture, analysts say, could help organizations run complex agent workloads more efficiently on existing infrastructure.

“Nemotron 3 Super combines Mamba’s linear-time sequence processing with Transformer attention and MoE routing, delivering higher throughput, lower latency, and better memory efficiency than pure transformers for long-context and multi-step workloads,” said Charlie Dai, VP and principal analyst at Forrester. “For enterprises, this translates into lower TCO, better utilization of on-prem or sovereign GPU clusters, and faster agent execution.”

Tulika Sheel, senior vice president at Kadence International, said the model’s architecture is designed to activate only a subset of parameters for each task, which helps improve efficiency.

“This design significantly improves throughput and lowers compute costs while maintaining accuracy,” Sheel said. “For enterprises, that can translate into faster inference, better performance on long-context workloads, and more cost-efficient deployment of large models.”

Open models reshape strategy

Open reasoning models are emerging as an option for enterprises seeking greater control over how AI systems are built and deployed. Research by McKinsey & Company attributes this interest to strong performance, ease of use, and lower implementation and maintenance costs compared with proprietary alternatives.

“As a result, many organizations may adopt a hybrid strategy, combining open models for internal workloads with proprietary models for external or high-performance tasks,” Sheel said. “Open reasoning models could push enterprises toward more customizable, self-hosted AI strategies rather than full reliance on proprietary platforms.”

Analysts also said that the ability to fine-tune and inspect models is becoming increasingly important as enterprises expand AI into regulated sectors such as finance, healthcare, and government.

“Open reasoning models give enterprises a credible alternative to proprietary foundation models by enabling fine-tuning, inspection, and on-prem deployment,” Dai said. “This supports customization for domain logic, regulatory compliance, and data residency, while reducing dependency on closed APIs and usage-based pricing.”

More Nvidia news:

- Nvidia partners with optics technology vendors Lumentum and Coherent to enhance AI infrastructure

- Nvidia partners with telecom providers for open 6G networks

- Nvidia plans a Windows PC SoC, setting up direct competition with Qualcomm, Intel, and AMD

- Nvidia lines up partners to boost security for industrial operations

- Meta scoops up more of Nvidia’s AI chip output

- Reports of Nvidia/OpenAI deal in jeopardy are overblown, says Nvidia’s CEO

- Eying AI factories, Nvidia buys bigger stake in CoreWeave

- China clears Nvidia H200 sales to tech giants, reshaping AI data center plans

- Nvidia is still working with suppliers on RAM chips for Rubin

- RISC-V chip designer SiFive integrates Nvidia NVLink Fusion to power AI data centers

- Nvidia H200 chips in China: US says yes, China says no

- Lenovo-Nvidia partnership targets faster AI infrastructure rollouts

Databricks buys Quotient AI to boost enterprise‑grade AI agent performance 12 Mar 2026, 12:20 am

Databricks has acquired Quotient AI, a provider of AI agent evaluation and training software, to help enterprises scale AI agents in production more reliably.

“Quotient AI was built to close the gap in agent evaluation and continual learning,” the company said in a statement, adding that the startup’s technology, infused inside its Genie and Agent Bricks offerings, will help enterprises monitor agent behavior in production, detect critical issues, and use those signals to improve agent performance continuously.

Addressing agent reliability in production

The acquisition, analysts say, aims to resolve a growing concern among CIOs trying to operationalize AI agents: while building prototypes has become relatively easy, proving that those systems behave reliably across complex enterprise workflows remains far harder.

“CIOs struggle to answer basic questions once AI agents are deployed in production: Why did it make that decision, will it behave the same tomorrow, and how do we verify it didn’t violate policy/compliance?” said Dion Hinchcliffe, lead of the CIO practice at The Futurum Group.

Quotient AI’s technology, Hinchcliffe added, will provide the evaluation frameworks and reinforcement learning feedback loops needed for enterprises to systematically measure agent performance, surface failures, and continuously help refine how those systems behave in real-world enterprise environments.

More importantly for CIOs, HyperFRAME Research’s practice leader of AI stack Stephanie Walter pointed out that Quotient’s technology isn’t about generic reinforcement learning (RL) for agents, but far more domain specific: “They want to help you train an agent that doesn’t just know how to code, but knows how to code for your specific data architecture in a way that passes your specific compliance checks.”

In fact, Ashish Chaturvedi, executive research leader at HFS Research, says Quotient AI’s team and technology are market-tested and credible as it led the quality improvement for GitHub Copilot, which, according to Chaturvedi, is one of the “few AI products that actually run at enterprise scale with real consequences for errors.”

Winds of change and competition

The acquisition is not Databricks’ only attempt at adding features that help enterprises run agents reliably at scale.

Earlier this year, the company introduced an Instructed Retriever approach designed to improve how enterprise AI systems fetch relevant information from internal data. Earlier this month, it unveiled KARL, an enterprise knowledge agent powered by custom reinforcement learning that can refine its responses based on feedback from real-world usage.

It’s not just Databricks, though; analysts say that most data platform vendors are targeting the same issues around scaling agents in productions although they might be starting at different points.

“Snowflake has been building its own evaluation tooling with Cortex Agent Evaluations and its Agent GPA framework. Teradata is taking yet another path entirely. Its Enterprise AgentStack and partnership with Google Cloud are anchored in governance, context, and hybrid deployment rather than in model-level evaluation or RL-driven improvement,” Chaturvedi said.

“The broader landscape is also moving. Dataiku has built evaluation integrations on top of Snowflake Cortex agents. LangChain’s ecosystem offers open-source alternatives like LangSmith for tracing. And the hyperscalers, AWS, Google, Microsoft, have their own observability and evaluation stacks that compete at the infrastructure layer,” Chaturvedi added.

Strategic moat

These moves from vendors, including Databricks, is however, more strategic and targeted towards building a competitive moat, the analyst further noted.

The idea here is that whichever data platform offers the best path to reliably scaling AI agents will eventually become sticky and preferable over the competition, Chaturvedi added.

That path, according to Hinchcliffe, seems to be agent evaluation, which he says is becoming the equivalent of CI/CD for AI agents, and enterprises will need pipelines that test agents against thousands of scenarios, measure behavior across complex workflows, and automatically improve performance over time.

“Platforms that own these feedback loops will compound their advantage, because every production deployment becomes training data for better agents. In that sense, Databricks isn’t just buying a tool for testing agents by acquiring Quotient AI; it’s investing in the control layer for the entire enterprise agent lifecycle,” Hinchcliffe added.

Microsoft’s .NET 11 Preview 2 offers cleaner stack traces 11 Mar 2026, 1:59 pm

Microsoft has published Preview 2 of its planned .NET 11 software development platform, emphasizing progress ranging from native runtime async to smaller SDK installers for Linux and macOS.

Released March 10, .NET 11 Preview 2 can be downloaded from net.microsoft.com. Preview 2 follows the February 10 release of Preview 1, with the production release expected in November.

Preview 2 brings significant progress toward runtime-native async, according to Microsoft. Instead of the compiler generating state-machine classes, the runtime itself manages async suspension and resumption. This produces cleaner stack traces, better debugging, and lower overhead. But runtime async is still a preview feature. The compiler must emit methods with MethodImplOptions.Async for the runtime to treat them as runtime-async.

Also in the runtime, the JIT now eliminates bounds checks for the common pattern where an index plus a constant is compared against a length. Checked arithmetic contexts that are proved redundant are also optimized away.